3 Mistakes You Make When Drawing the Figure

Don’t you sometimes wish you could apply the keyboard’s “undo” shortcut to life? When we make a mistake, and all of us do, the first response should be to acknowledge and then correct it. Easier said than done, yes? When it comes to art, specifically figure drawing, it’s relatively easy to do. Because with Stan Prokopenko’s guidance, you can learn how to acknowledge the mistakes, and then how to fix them. With practice, you’ll find that it becomes easier to draw accurately the first time.

3 Common Mistakes When Drawing the Figure by Stan Prokopenko

We like to think that we are completely unique, that our problems are different. How could that talented 13-year-old boy from India be making the same drawing mistakes as the 75-year-old German man who recently decided he wants to explore his creativity? The truth is we have a lot more in common than we think. I’ve looked at the drawings of hundreds, if not thousands, of students asking for critiques. The similarities are amazing. Of course, in many subtle ways, we are different, but the fundamental drawing errors we make are incredibly similar. Here are three common issues. Unless you’re a seasoned draftsman, chances are you have trouble with some or all of these. My hope is this list will help you identify your own mistakes and guide you toward smarter practice.

Mistake #1 – Your proportions are out of control!

How could I not start with this one? We all need to tune our eyes to see accurate shapes. Even those with a “photographic memory” have to polish their gifts.

A good exercise is to draw something complex, attempting complete accuracy. Measure a lot. Use your pencil to measure size relationships. Judge angles between shapes. Use horizontal and vertical plumb lines to observe placement relationships between shapes. My course on Measuring in the Figure Drawing will give you everything you need to measure correctly.

Identifying and then fixing your mistakes is the key. Having a good instructor identify your mistakes is useful, but proportion mistakes can be easily identified on your own. If you’re drawing from a photo, scan your drawing and lay it over the photo in Photoshop. There you go. All of your mistakes are right in front of you. If you don’t like using digital tools, you can draw it on a sheet of tracing paper, and put it over the photo to check your mistakes.

At first, you will make a lot of mistakes. I mean a lot… Because there are so many things to measure and analyze, there are just too many things that could go wrong. You can’t possibly measure everything, but the process of making those mistakes, identifying them and then attempting it again without making the same mistakes–that process is the way you train your brain to do the work for you. Eventually you won’t have to measure as much. You’ll build the neuropathways in your brain to do it at lightning speeds. Your subconscious will take over and make it easy.

Mistake #2: You’re copying the contours.

Do you understand what you’re drawing and why, or are you just copying the outlines? It’s important that you try to either find the flow of the forms (gesture) or construct the 3D forms (structure). This requires more effort, more mental energy, so naturally you fall back on copying what you see.

Gesture – During the early stages of the drawing, focus more on gesture. Find the motion between the forms. Focus on the posture, the emotion, the action being performed. Don’t get distracted by the shapes of the muscles. Use simple lines to describe the motion – only C curves, S curves, or straight lines. A common way to force us to simplify is to set a time limit. But make sure this doesn’t just cause you to move your hand faster. The purpose isn’t to draw more in less time. It’s to draw less and simplify. Draw only the few simple lines required to capture the pose.

Structure – once the gesture is identified and you’re generally satisfied with the proportions, then what? Your brain is going to tell you to add more details to the gesture with some more accurate contours. STOP! Tell your brain to shut up! It’s time to add some structure. This also involves simplifying, but this time, you’re simplifying the 3d forms. That rib cage can be an egg-like shape, or a box. The pelvis can be a cylinder, or box. The limbs can be cylinders or boxes. Actually anything can be simplified into a box. A box has distinct top, bottom, front, back and side planes. A cylinder has only top and bottom, but no clear division between the front back and sides. A ball… well, it looks like a circle from any angle.

In my Figure Drawing course, I progress through increasingly difficult exercises for structure. You start with The Bean – simplifying the torso into two balls inside of a sock. This helps you identify the leaning, tilting, and twisting of the torso. It helps you think of squashing and stretching without getting distracted with contour.

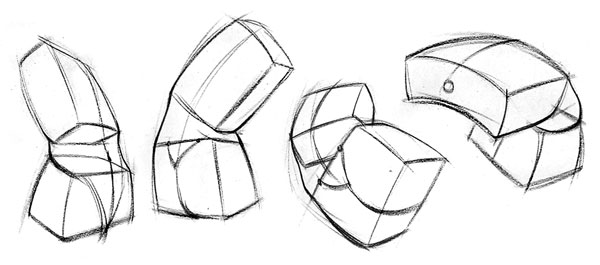

Then you progress to The Robo Bean – simplifying the torso into two boxes. Same as The Bean, but now you have to draw all the planes. You have to think of perspective. How are the rib cage and pelvis oriented in space? As you can imagine, this will give your figure drawings a much better feeling of 3-dimensionality.

Finally, you progress to Mannequinization – simplifying the smaller anatomical forms into simple geometric shapes. Instead of just a box for the torso, you consider the planes of the deltoids, pecs, lats, etc.. Still not contour – these are simple geometric shapes in perspective.

Now you can put in that contour. And it’s really easy after you’ve laid in the groundwork of the gesture and structure.

Mistake #3: You’re afraid of the dark.

I’m not talking about the monsters under your bed. I mean the dark values when shading. Especially when shading skin, you tend to avoid dark values. The weird thing is, this tends to be true even when drawing someone with dark skin. I think this stems from our fear to commit and make a mistake. Dark values are hard to erase, so, you just avoid them. Of course, this hurts your drawing because shadows are important. The light and dark planes show the 3D forms. You can show 3D forms with perspective lines like I just described, but in reality there are no lines. Lines just represent the edges between the planes. After you construct the forms with lines, the next step is to convert them to tone.

Start by separating the shadow family from the light family. It helps to map in the core shadows first, so you can see the shape design before actually committing to those dark values. Then, fill in the shadow side with a middle value. This will be the lightest you can go inside the shadow family. Remember – the darkest light is lighter than the lightest dark (read that a few times). Finally, add the subtle details – the halftones, highlights, and dark accents. ~Stan Prokopenko

Get even more in-depth instruction from Prokopenko when you take his video workshops. They include Portrait Drawing Fundamentals and Figure Drawing Fundamentals.

Until next time,

Cherie

**Subscribe to the Artists Network newsletter for inspiration, instruction, and ideas, and score a free download on Human Figure Drawing: A Two-Part Guide by Sadie J. Valeri.

Thank you! I’ve been progressing through the years and this article really rezonates with the struggles i’ve been having while drawing the figure.